Call us

+86-21-56666351Modern street lighting control systems work by combining sensors, communication hardware, and centralized management software to automate when lights turn on, off, or dim. These systems allow a city to reduce energy waste, improve maintenance efficiency, and respond dynamically to environmental conditions or safety needs. Instead of relying on a single type of device—such as a basic dusk-to-dawn sensor—today’s smart lighting networks use layered controls that integrate data, connectivity, and long-term asset management.

For many municipalities, upgrading to an intelligent control framework is no longer optional; it is a necessary evolution to support safer streets, reduced carbon emissions, and scalable urban infrastructure. Understanding how these systems operate helps clarify why networked lighting has quickly become the global standard.

Street lighting has transitioned through several generations of technology, each reflecting different priorities—first reliability, then automation, and now intelligence. Historically, city engineers relied on manual switching or simple time clocks to illuminate roadways. These methods, while predictable, lacked flexibility and often resulted in lights operating during daylight or failing to activate at dusk.

The arrival of photocell-based automation marked a significant improvement. A street light photocell sensor detects ambient brightness and activates the luminaire at sunset. This decentralized approach ensured self-contained control, reducing dependency on mechanical timers and centralized wiring. However, photocells also introduced limitations: environmental sensitivity, inconsistent switching times, and limited monitoring capability.

As cities modernized, the demand for more coordinated infrastructure led to two major innovations:

Cabinet-level controllers, which manage large lighting zones from a central point

Fully networked lighting systems, which connect each luminaire to a digital platform

These new generations enable fine-grained control, real-time diagnostics, and energy optimization, all of which are increasingly important in sustainable city planning.

A contemporary lighting control system includes multiple interconnected layers. Each element has a specific role, and together they create a flexible and resilient infrastructure.

At the foundation of the system are the components that monitor environmental conditions or operational status. This layer traditionally included basic photocells, but now encompasses a broader range of technology.

For example, a luminaire equipped with a dedicated sensing module may use a light sensor bulb socket to house its detection hardware. This arrangement allows the system to measure ambient light or activity levels, feeding data into the controller so it can determine when illumination is required. Some street lights also use motion or presence sensors for adaptive lighting, which brightens the luminaire when vehicles or pedestrians approach.

While photocells remain relevant, many cities are gradually integrating more sophisticated sensor arrays, enabling a shift toward predictive and adaptive control rather than simple on/off detection.

The hardware that connects sensors or controllers to the luminaire plays an essential role in ensuring compatibility and flexibility. For decades, the industry has relied on standardized interfaces that allow components from different vendors to interoperate.

The nema photocell receptacle, for example, continues to be widely used in North America. It supports plug-and-play installation of photocells, network nodes, or accessories, allowing municipalities to change control strategies without replacing entire fixtures. In Europe and other regions where modularity is prioritized, the zhaga receptacle has grown in popularity thanks to its compact design and support for next-generation devices.

Similarly, many luminaires include the zhaga book 18 socket, which enables quick swapping of sensing or communication modules without recabling the fixture. This modular design philosophy is critical for cities that expect to upgrade system capabilities over time as smart-city technologies evolve.

The control layer determines how each luminaire behaves. Some systems use cabinet-based controllers, while others rely on individual fixture-level devices. The choice depends on the city’s infrastructure design and long-term management strategy.

A basic dusk-to-dawn luminaire may use a traditional photocell component such as a LongJoin photocell, which provides standalone brightness sensing with no need for network integration. Other installations incorporate specialized modules that support particular wiring configurations or operational needs, such as a LongJoin jl 103a or a LongJoin jl 202a, each of which is selected according to the fixture’s electrical architecture. More advanced projects may choose devices like a LongJoin jl 205c, which integrates seamlessly with mid-level control systems or specific luminaire families.

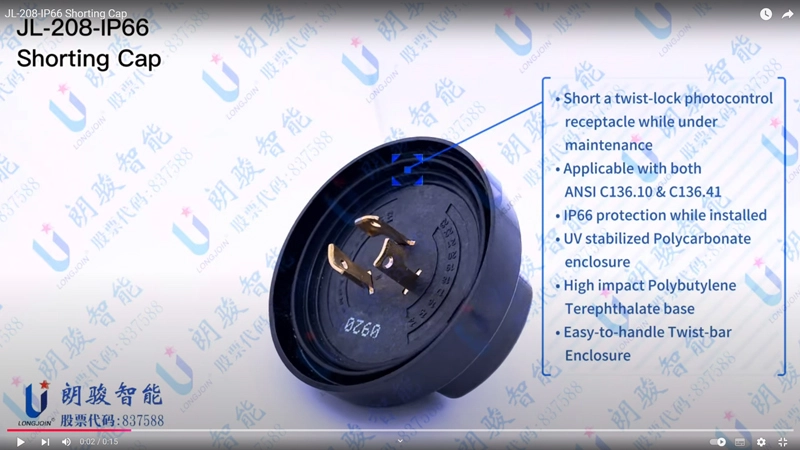

When a project transitions from photocell-based automation to centralized or networked control, installers commonly use accessories such as the jl 208 shorting cap, which bypasses sensor functionality and allows the luminaire to follow an upstream controller. This flexibility makes hardware transitions smoother and minimizes downtime during municipal upgrades.

At the heart of a modern system is communication. Networked street lights share data with a central management platform, enabling real-time visibility into every fixture’s status, energy use, and operational conditions.

Communication technologies include:

RF mesh networks

Cellular modules (4G/5G)

LoRaWAN

Powerline communication (PLC)

Wi-Fi or hybrid protocols in dense urban corridors

These technologies allow thousands of luminaires to communicate without manual intervention. The system can instantly identify outages, voltage problems, or abnormal behavior. This eliminates traditional patrol-based maintenance and shortens repair times, improving public safety and reducing labor costs.

The system’s intelligence resides in a cloud-based or local management platform that aggregates data and issues commands. Operators can view performance dashboards, schedule dimming profiles, or analyze energy trends.

Key features typically include:

Map-based visualization of assets

Configurable lighting schedules

Remote activation and dimming

Predictive maintenance alerts

Energy and cost reporting

Integration with emergency or smart-city platforms

In cities where resiliency is a priority, the software can autonomously adjust lighting levels during extreme weather, power fluctuations, or unexpected traffic events.

The global movement toward intelligent lighting is being driven by several factors: sustainability goals, labor shortages, public safety priorities, and the wider adoption of smart-city infrastructure.

Lighting can represent 30–60% of a city’s total electricity use. Networked systems allow for advanced dimming strategies that can reduce consumption by up to 75% compared to traditional dusk-to-dawn systems. Cities can:

Lower brightness during low-traffic hours

Increase output during events or emergencies

Apply dynamic dimming based on sensor feedback

These capabilities reduce strain on the electrical grid and support decarbonization initiatives.

Rather than waiting for citizen reports or conducting manual inspections, cities with intelligent lighting systems receive automatic failure notifications. Maintenance teams can prioritize the most critical issues and avoid unnecessary service trips.

This is especially beneficial for large cities—where a single technician might be responsible for 10,000 or more luminaires—and for regions where safety risks increase significantly when outages go unaddressed.

Well-designed lighting networks allow operators to adjust brightness dynamically in response to real-time conditions. Areas with high pedestrian traffic can be illuminated more brightly, while parks or low-activity areas may be dimmed to reduce light pollution.

Adaptive lighting supports:

Accident prevention

Crime reduction

Navigation during extreme weather

Improved nighttime visibility for pedestrians and cyclists

Emergency services can also request temporary lighting changes to support operations.

Cities around the world are building interconnected digital ecosystems. Lighting poles are increasingly used to host sensors, cameras, communication modules, and small-cell wireless equipment.

Smart lighting control systems provide the backbone for these applications, making them essential for:

Environmental monitoring

Traffic analytics

Smart parking

Public Wi-Fi

Disaster response systems

Without networked lighting infrastructure, these solutions become more expensive and harder to deploy.

Even as cities embrace networked solutions, many still rely on traditional controls. This coexistence is possible because the lighting industry maintains strong backward compatibility.

For example:

A nema shorting cap can support centralized control even when the luminaire hardware originally relied on photocells.

Interfaces like NEMA and Zhaga ensure modularity, allowing fixtures to evolve alongside city requirements.

Support from street light controller manufacturers helps municipalities implement hybrid solutions during the transition period.

The result is a system architecture that balances innovation with practicality.

While the benefits are substantial, the transition to smart lighting also presents challenges:

Though long-term savings outweigh the costs, the upfront installation of nodes, communication equipment, and management platforms can strain municipal budgets. Grants, energy-performance contracts, and phased deployment strategies help mitigate this issue.

Any connected infrastructure must be protected against unauthorized access. Reputable system providers follow best practices in encryption, authentication, and network segmentation to safeguard critical urban operations.

Cities must evaluate which interfaces—NEMA, Zhaga, proprietary modules, or hybrid systems—best meet their long-term needs. Choosing standards-based components ensures broader vendor compatibility and reduces lifecycle risk.

Over the next decade, street lighting will continue evolving into a multifunctional urban platform. Anticipated advancements include:

AI-driven lighting algorithms

Integration with autonomous vehicle systems

Real-time air-quality monitoring

Predictive maintenance using machine learning

Seamless alignment with renewable energy grids

As sensors and network nodes become more compact and energy-efficient, luminaires will serve as critical data hubs throughout modern cities.

A smart system connects luminaires to a communication network and central software, enabling dimming schedules, remote monitoring, and data analytics—capabilities a photocell cannot provide.

Yes. Many fixtures with standardized interfaces can be upgraded using network nodes, shorting caps, or modular receptacles.

Some hybrid deployments use photocells at the fixture level, but most advanced systems replace them with network nodes for greater flexibility.

Depending on dimming strategies and sensor use, cities can achieve 40–75% reductions in electricity consumption.

Networked systems typically reduce maintenance workload thanks to automated alerts and real-time diagnostics.

[1]. International Electrotechnical Commission. “IEC 62722-2-1: Luminaire Performance Requirements.”

[2]. Illuminating Engineering Society. “ANSI/IES RP-8: Recommended Practice for Roadway and Parking Facility Lighting.”

[3]. IEEE Standards Association. “IEEE P2144: Standard for Smart Street Lighting Systems.”

Address:

2nd Floor, Building 8, 129 Hulan West Road, Baoshan District, Shanghai, China